HERBERT BAYER

[1900-1985]

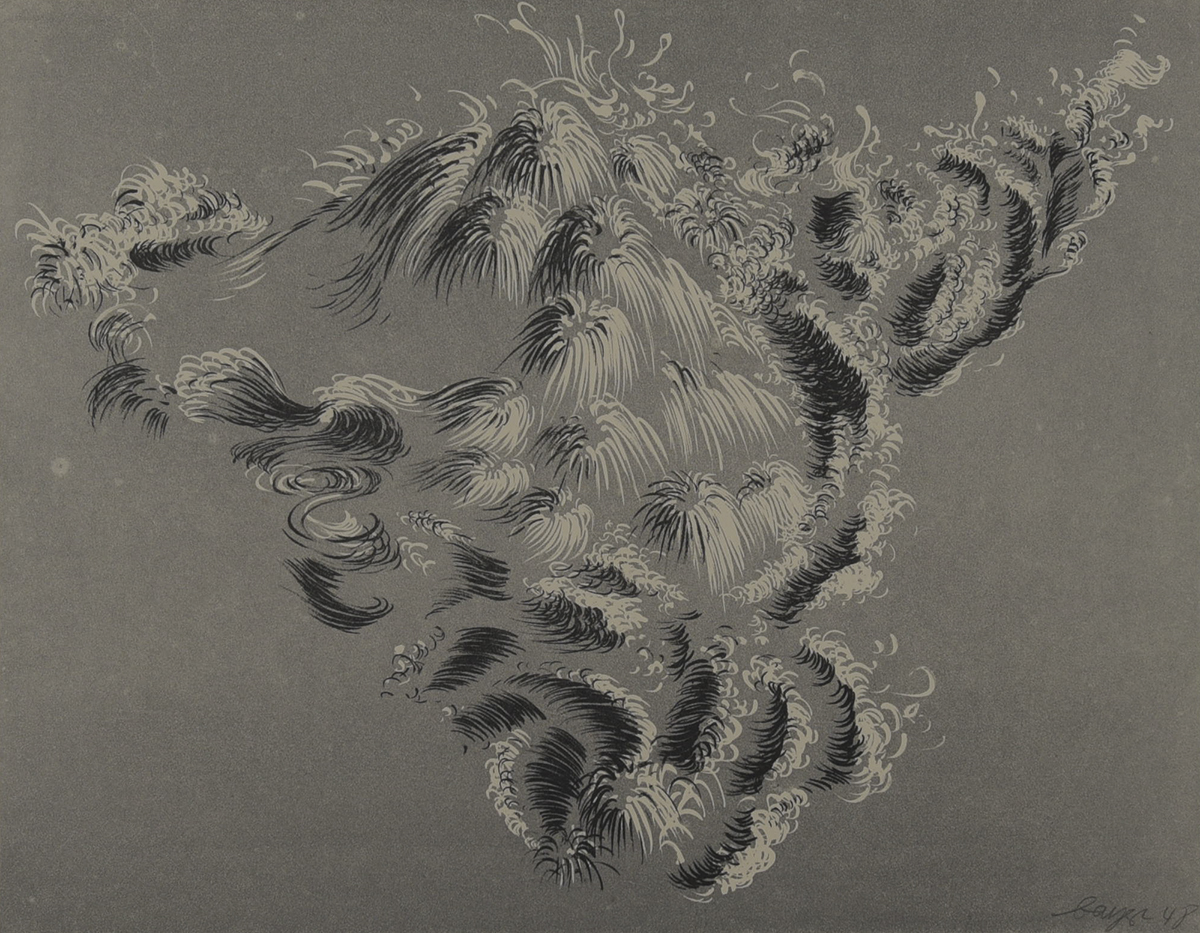

Seven Convolutions, 1948 | 22"x18" color lithograph prints on paper

Bayer rediscovers his passion for mountains and their formations while cross-country skiing in Vermont. An important series of paintings emerge called “Mountains and Convolutions.” After moving to Colorado, he has a brief connection to Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center and executes this series of seven two-color lithographs based on the “Mountains and Convolutions’ paintings in an edition of ninety. He created these works with the master lithographer Lawrence Barrett. These lithographs represent the continued vigor of elemental forms in nature.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY:

He enjoyed a versatile sixty-year career spanning Europe and America that included abstract and surrealist painting, sculpture, environmental art, industrial design, architecture, murals, graphic design, lithography, photography and tapestry. He was one of the few “total artists” of the twentieth century, producing works that “expressed the needs of an industrial age as well as mirroring the advanced tendencies of the avant-garde.”

One of four children of a tax revenue officer growing up in a village in the Austrian Salzkammergut lake region, Bayer developed a love of nature and life-long attachment to the mountains. A devotee of the Vienna Secession and the Vienna Workshops (Wiener Werkstätte) whose style influenced Bauhaus craftsmen in the 1920s, his dream of studying at the Academy of Art in Vienna was dashed at age seventeen by his father’s premature death.

In 1919 Bayer began an apprenticeship with architect and designer, Georg Schmidthamer, where he produced his first typographic works. Later that same year he moved to Darmstadt, Germany, to work at the Mathildenhöhe Artists’ Colony with architect Emanuel Josef Margold of the Viennese School. As his working apprentice, Bayer first learned about the design of packages – something entirely new at the time – as well as the design of interiors and graphics of a decorative expressionist style, all of which later figured in his professional career.

While at Darmstadt, he came across Wassily Kandinsky’s book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, and learned of the new art school, the Weimar Bauhaus, in which he enrolled in 1921. He initially attended Johannes Itten’s preliminary course, followed by Wassily Kandinsky’s workshop on mural painting. Bayer later recalled, “The early years at the Bauhaus in Weimar became the formative experience of my subsequent work.” Following graduation in 1925, he was appointed head of the newly-created workshop for print and advertising at the Dessau Bauhaus that also produced the school’s own print works. During this time he designed the “Universal” typeface emphasizing legibility by removing the ornaments from letterforms (serifs).

Three years later he left the Bauhaus to focus more on his own artwork, moving to Berlin where he worked as a graphic designer in advertising and as an artistic director of the Dorland Studio advertising agency. (Forty years later he designed a vast traveling exhibition, catalog and poster -- 50 Jahre Bauhaus -- shown in Germany, South America, Japan, Canada and the United States.) In pre-World War II Berlin he also pursued the design of exhibitions, painting, photography and photomontage, and was art director of Vogue magazine in Paris. On account of his previous association with the Bauhaus, the German Nazis removed his paintings from German museums and included him among the artists in a large exhibition entitled Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) that toured German and Austrian museums in 1937.

His inclusion in that exhibition and the worsening political conditions in Nazi Germany prompted him to travel to New York that year with Marcel Breuer, meeting with former Bauhaus colleagues, Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy to explore the possibilities of employment after immigration to the United States. In 1938 Bayer permanently relocated to the United States, settling in New York where he had a long and distinguished career in practically every aspect of the graphic arts, working for drug companies, magazines, department stores, and industrial corporations. In 1938 he arranged the exhibition, “Bauhaus 1919-1928” at the Museum of Modern Art, followed later by “Road to Victory” (1942, directed by Edward Steichen), “Airways to Peace” (1943) and “Art in Progress” (1944).

Bayer’s designs for “Modern Art in Advertising” (1945), an exhibition of the Container Corporation of America (CAA) at the Art Institute of Chicago, earned him the support and friendship of Walter Paepcke, the corporation’s president and chairman of the board. Paepcke, whose embrace of modern currents and design changed the look of American advertising and industry, hired him to move to Aspen, Colorado, in 1946 as a design consultant transforming the moribund mountain town into a ski resort and a cultural center. Over the next twenty-eight years he became an influential catalyst in the community as a painter, graphic designer, architect and landscape designer, also serving as a design consultant for the Aspen Cultural Center.

In the summer of 1949 Bayer promoted through poster design and other design work Paepcke’s Goethe Bicentennial Convocation attended by 2,000 visitors to Aspen and highlighted by the participation of Albert Schweitzer, Arthur Rubenstein, Jose Ortega y Gasset and Thornton Wilder. The celebration, held in a tent designed by Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, led to the establishment that same year of the world-famous Aspen Music Festival and School regarded as one of the top classical music venues in the United States, and the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies in (now the Aspen Institute), promoting in Paepcke’s words “the cross fertilization of men’s minds.”

In 1946 Bayer completed his first architecture design project in Aspen, the Sundeck Ski Restaurant, at an elevation of 11,300 feet on Ajax Mountain. Three years later he built his first studio on Red Mountain, followed by a home which he sold in 1953 to Robert O. Anderson, founder of the Atlantic Richfield Company who became very active in the Aspen Institute. Bayer later designed Anderson’s terrace home in Aspen (1962) and a private chapel for the Anderson family in Valley Hondo, New Mexico (1963).

Transplanting German Bauhaus design to the Colorado Rockies, Bayer created along with associate architect, Fredric Benedict, a series of buildings for the modern Aspen Institute complex: Koch Seminar Building (1952), Aspen Meadows guest chalets and Center Building (both 1954), Health Center and Aspen Meadows Restaurant (Copper Kettle, both 1955). For the grounds of the Aspen Institute in 1955 Bayer executed the Marble Garden and conceived the Grass Mound, the first recorded “earthwork” environment. In 1973-74 he completed Anderson Park for the Institute, a continuation of his fascination with environmental earth art.

In 1961 he designed the Walter Paepcke Auditorium and Memorial Building, completing three years later his most ambitious and original design project – the Musical Festival Tent for the Music Associates of Aspen. (In 2000 the tent was replaced with a design by Harry Teague.) One of Bayer’s ambitious plans from the 1950s, unrealized due to Paepcke’s death in 1960, was an architectural village on the outskirts of the Aspen Institute, featuring seventeen of the world’s most notable architects – Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, I.M. Pei, Minoru Yamasaki, Edward Durrell Stone and Phillip Johnson – who accepted his offer to design and build houses.

Concurrent with Bayer’s design and consultant work while based in Aspen for almost thirty years, he continued painting, printing making and mural work. Shortly after relocating to Colorado, he further developed his “Mountains and Convolutions” series begun in Vermont in 1944, exploring nature’s fury and repose. Seeing mountains as “simplified forms reduced to sculptural surface in motion,” he executed in 1948 a series of seven two-color lithographs (edition of 90) for the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Colorado’s multi-planal typography similarly inspired Verdure, a large mural commissioned by Walter Gropius for the Harkness Commons Building at Harvard University (1950), and a large exterior sgraffito mural for the Koch Seminar Building at the Aspen Institute (1953).

Having exhausted by that time the subject matter of “Mountains and Convulsions,” Bayer returned to geometric abstractions which he pursued over the next three decades. In 1954 he started the “Linear Structure” series containing a richly-colored balance format with bands of sticks of continuously modulated colors. That same year he did a small group of paintings, “Forces of Time,” expressionist abstractions exploring the temporal dimension of nature’s seasonal moulting. He also debuted a “Moon and Structure” series in which constructed, architectural form served as the underpinning for the elaboration of color variations and transformations.

Geometric abstraction likewise appeared his free-standing metal sculpture, Kaleidoscreen (1957), a large experimental project for ALCOA (Aluminum Corporation of America) installed as an outdoor space divider on the Aspen Meadows in the Aspen Institute complex. Composed of seven prefabricated, multi-colored and textured panels, they could be turned ninety degrees to intersect and form a continuous plane in which the panels recomposed like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. He similarly used prefabricated elements for Articulated Wall, a very tall free-standing sculpture commissioned for the Olympic Games in Mexico City in 1968. A similar piece is now on permanent display at the Design Center in Denver, Colorado.

In the 1960s Bayer began investigating the interactive relationship between light and color in the “Monochromatics” series, yielding a large chromatic number of paintings, drawings and lithographs over the next decade. In 1968 Edition Dombergrer in Stuttgart, Germany, published a portfolio of six serigraphs based on his chromatic paintings. Originating in the Vorkurs movement established at the Bauhaus by Johannes Itten to experiment with materials, spatial arrangements and color as abstract alignments and compositions, Bayer’s chromatic paintings represent the culmination of his research into pure color and geometry. Employing circles, squares, curves, triangles, etc., the paintings have perfect form and generous coloration without jarring optical illusions or conflict.

In Colorado in the early 1970s Bayer’s Fall Geometry (1973) – related to his “Mountains and Convulsions” series created some twenty years earlier – conveys the shifting attitude of light and color in the universe with changes of the seasons. After relocating to Montecito, California, in 1974 Bayer designed Anaconda, a large white marble sculpture of various geometric shapes placed in a shallow reflecting pool against a background mural of perforated bronze squares (designed by Matthias Goeritz) in the main lobby of the Anaconda Building in downtown Denver.

In 1973 a major Bayer retrospective was organized by Gwen Chanzit, curator of the Herbert Bayer Archive at the Denver Art Museum. It documented his s viewthat, “The creative process is not performed by a skilled hand alone, or by intellect alone, but must be a unified process in which ‘head, heart and hand’ play a simultaneous role."

Herbert Bayer received numerous awards and honors, including an honorary doctorate from the Technische Hochschule (Graz, Austria), the Österrichisches Ehrenkreutz für Wissenschaft und Kunst, the Kulturpreis für Fotografie (Cologne, Germany), and the Ambassador’s Award (London).

Solo Exhibitions: Galerie Povolozky, Paris (1929); Bauhaus, Dessau (1931); London Gallery, London (1937); Black Mountain College, North Carolina (1940); Willard Gallery, New York (1943); Cleveland Institute of Art (1952); Schaeffer Galleries, New York (1953); Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, Colorado (1955, 1964); Andrew Morris Gallery, New York (1963); Byron Gallery, New York and Esther Robles Gallery, Los Angeles (1965); Philadelphia Art Alliance (1967); Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg (1970); Österrichisches Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna (1971); Saidenberg Gallery, New York (1983); Janus Gallery, Los Angeles (1983); Kent Gallery, New York (1995, 1997); “Herbert Bayer Centennial,” Kent Gallery, New York; Kamakura Gallery, Japan; and Aspen Center for Humanities, Colorado (2000).

Traveling Retrospective Exhibitions: “The Way Beyond Art,” originating at Brown University (1947-49); various museums in Germany, Austria and Switzerland (1956-57); Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Duisburg, sent to other museums in Germany, Italy and the United States, including the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center (1962); Haus Deutscher Ring, Hamburg, and other museums in Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, Canada and Venzuela (1974-78); American Federation of the Arts circulated to museums in New Hampshire, New York, Georgia and California (1977-78); and exhibition of Bayer’s photographic works organized by ARCO Center for Visual Art, Los Angeles, and circulated to museums throughout the United States (1977-78).

Group Exhibitions (selected): Julian Levy Gallery, New York (1931-34); “Bauhaus,” (1938), “Art and Advertising,” (1943), Museum of Modern Art, New York; “Annual Exhibition of Western Artists,” Denver Art Museum (1952-65); Alliance Graphique Internationale, Paris (1956); “Biennale,” Sao Paulo Brazil (1959); “American Abstract Artists,” New York (1959-6); Arts Club of Chicago (1962).

Museum Collections: Whitney Museum of American Art, Guggenheim Museum and Museum of Modern Art, all in New York; Fogg Art Museum-Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut; Oklahoma City Museum of Art; Santa Barbara Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Bayer Photographic Archive; University of Arizona, Tucson; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center; Denver Art Museum; Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art, Denver; numerous public collections in Germany, Italy and Mexico.